Class Hierarchy

Object

All core Unity classes inherit from the Object class:

Object

├── GameObject

├── Component

│ ├── Transform

│ └── Behaviour

│ ├── MonoBehaviour

│ │ ├── YourScript_1

│ │ └── YourScript_2

│ ├── Renderer

│ ├── Collider

│ ├── Rigidbody

│ ├── Camera

│ ├── Light

│ └── AudioSource

├── Material

├── Texture

└── AudioClip

If you look at the documentation, you notice that this class provides some important elements:

Category |

Member |

Description |

|---|---|---|

Property |

string name |

Returns the name of the object |

Public Method |

int GetInstanceID() |

Returns a unique integer identifying the object |

Static Method |

void Destroy(Object obj) |

Destroys the specified object |

Static Method |

Object Instantiate(Object obj) |

Creates and returns a copy of the specified object |

Since Unity scripts inherit from MonoBehaviour which inherits from Object, you can call Destroy directly in the code, like a regular method:

using UnityEngine;

public class MyScript : MonoBehaviour

{

void Start() {}

void Update()

{

Destroy(...);

}

}

The Destroy method can destroy any Unity object, since all Unity objects inherit from the Object class.

Object modeling

Object-oriented programming offers two main ways to build a complex class: inheritance or aggregation.

Inheritance creates a specialized class from an existing base class. For example, to create a Wizard class, you derive it from a Human class and add new methods for magical abilities.

Aggregation assembles multiple objects to form a more complete one. To create a Wizard, inside the Human class, you add a list of talents and abilities where you insert all the powers a magician can perform.

The inheritance way, especially in video games, is very limiting:

Each variation of the Wizard (Paladin, Necromancer, etc.) requires creating a new class

Classes are defined at compile time. Adding a new ability during the game, such as potion making, is not allowed

This approach can lead to managing a large number of classes, making the system harder to maintain and extend

Thus, in video game development, the aggregation approach has proven to be the most flexible, intuitive, and efficient modeling technique. So, in Unity, you must see a GameObject as an empty container. When you want to define a specific GameObject, such as a player, a door, or a car, you add specific Components to this GameObject.

GameObject

Everything that exists in a 2D/3D scene is a GameObject, for example:

a car

a wall

a camera

a character

a spawn point

Documentation

Let’s have a look at the documentation of the GameObject class. When you scroll down, you will notice a section called : Inherited Members where you will find all the methods and properties inherited from the Object class: name, Destroy, Instantiate…

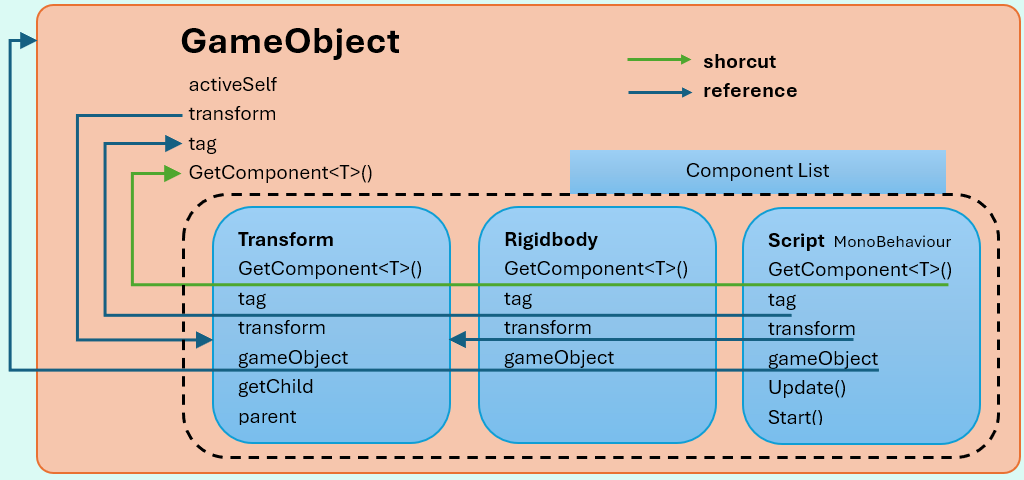

Now, let us examine the elements of a GameObject:

Category |

Member |

Description |

|---|---|---|

Property |

string tag |

Describes the category the GameObject belongs to (Enemy, Ground, Spawner, etc.) |

Property |

Transform transform |

Reference to the Transform component attached to the GameObject (read-only) |

Property |

bool activeSelf |

Indicates whether the GameObject is active (true) or inactive (false) (read-only) |

Public Method |

void SetActive(bool value) |

Activates or deactivates the GameObject |

Public Method |

Component AddComponent(Type componentType) |

Instantiate and adds a component of the specified type to the GameObject |

Public Method |

T GetComponent<T>() |

Retrieves the first component of type T attached to the GameObject |

Most of the time, a gameobject has only one component of each type: a single Rigidbody, a single MeshRenderer, or a single Collider. Therefore, the method GetComponent<Type>() allows us to find the component you need easily.

Category |

Member |

Description |

|---|---|---|

Static Method |

GameObject FindWithTag(string tag) |

Retrieves the first active GameObject tagged with the specified tag |

Static Method |

GameObject Find(string name) |

Finds and returns a GameObject with the specified name |

As the official documentation said: GameObject.Find causes significant performance degradation at scale and is not recommended for performance-critical code, especially in the script/Update function. Find searches the entire scene, the search is linear, checking each GameObject one by one traversing the hierarchy. The result is not cached and every call performs the full search again. The more GameObjects you have and the more frequently you call GameObject.Find, the greater the impact on your application’s performance. Instead, cache the result in a member variable at startup, or use GameObject.FindWithTag.

Ranking of methods from fastest to slowest:

Method |

Performance |

Notes |

|---|---|---|

Direct reference ([SerializeField]) |

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ |

Fastest method. No search. Reference assigned directly in the Inspector. |

GetComponent |

⭐⭐⭐⭐ |

Very fast. Searches only within the same GameObject. |

GameObject.FindWithTag |

⭐⭐⭐ |

Moderate performance cost because your game generally uses a limited number of tags |

GameObject.Find |

⭐ |

Slowest. Searches through all active GameObjects. Should be avoided in performance-critical code. |

Component

Introduction

A GameObject contains Components, which define how it looks and behaves. Examples of Components:

Transform : position, rotation, scale

MeshRenderer : renders the mesh using a Material and a Shader

MeshFilter : stores the mesh data (geometry: vertices, triangles, normals, UVs)

Collider : collision detection

Rigidbody : physics simulation

Script (MonoBehaviour) : custom logic

Animator : controls animations using an Animator Controller

CharacterController : specialized Component for character movement

Light : illuminates the scene

Avertissement

Any GameObject contains exactly one mandatory Component: the Transform.

Example of a typical NPC GameObject:

GameObject NPC

├── Transform (position)

├── MeshRenderer (appearance)

├── Scripts (AI, health, etc.)

├── AudioSource (footsteps, voice)

└── CharacterController (movement & collision for characters)

Other examples:

Player: NPC components, Script (PlayerController: keyboard/joystick input), Camera, AudioListener

House: Transform, MeshFilter (geometry), MeshRenderer (Materials and Shaders), Collider

Spawner: Transform, Script (Spawner: contains the logic to instantiate enemies), invisible entity

Light: Transform, Light (illuminates the scene)

Projectile (bullet, arrow, etc.): Transform, MeshFilter, MeshRenderer, Collider, Rigidbody, Script (damage logic)

Documentation

Lets have a look at the documentation of the Component class. When you scroll down, you will notice a section called : Inherited Members where you will find all the methods and properties inherited from the Object class: name, Destroy, Instantiate… Now, let us examine the elements of a Component:

Category |

Member |

Description |

|---|---|---|

Property |

gameObject |

reference the game object this component is attached to |

Property |

transform |

reference the transform component of the associated gameobject |

Property |

tag |

reference the tag of the associated gameobject |

A syntactic sugar is syntax designed to make code easier to read. It makes the language « sweeter » by allowing things to be expressed more concisely. The drawback is that developers might become confused. For example, the tag property is not the tag of the component, it is a reference to the tag property of the gameobject the component is attached to. Beware of confusion.

An even more subtle point, when you write:

*GetComponent<T>()*

This syntax is a shorcut for calling gameObject.GetComponent<T>(). Do not get confused: a Component does NOT contain other components. When you call GetComponent<Rigidbody>(), the request is performed on the the gameobject.

The Transform component

Introduction

This component:

is automatically added when the GameObject is created

cannot be removed

defines the position, rotation, and scale of the object

Since the Transform component is always present, it can be accessed directly using the transform reference defined everywhere. This avoids the need to write gameObject.GetComponent<Transform>().

Documentation

Lets have a look at the documentation of the Transform class. When you scroll down, you will notice a section called : Inherited Members where you will find all the methods and properties inherited from the Object class: name, Destroy, Instantiate…

Scene Hierarchy

The Transform component defines the position, rotation, and scale of a GameObject. But this component is special because it also describes the scene hierarchy :

Category |

Member |

Description |

|---|---|---|

Property |

Transform parent |

Reference to the parent Transform of this Transform. |

Property |

int childCount |

The number of children this Transform has. |

Public Method |

Transform GetChild(int index) |

Returns the child Transform at the specified index. |

Thus, these properties enable traversal of the entire scene hierarchy. This may seem surprising, since one might initially assume that the hierarchy involves GameObjects, whereas it is actually based on Transforms. This is not an issue, since each Transform in the hierarchy maintains a reference to its associated GameObject.

Behaviour

Object

└── Component

├── Transform

└── Behaviour

├── MonoBehaviour

├── Renderer

│ ├── MeshRenderer

│ └── SkinnedMeshRenderer

├── Collider

│ ├── BoxCollider

│ ├── SphereCollider

│ └── CapsuleCollider

├── Rigidbody

├── Camera

├── Light

└── AudioSource

The Behaviour class adds the enabled property, allowing components to be enabled or disabled. Most Unity components inherit from Behaviour, such as MonoBehaviour, Renderer, and Collider. The Transform component is the only exception and cannot be disabled.

Scripts

A script is a class that derives from MonoBehaviour. MonoBehaviour inherits from Behaviour, which in turn inherits from Component. In Unity, all gameplay logic is implemented through scripts.

Message methods

The MonoBehaviour class introduces two main message methods: Start() and Update(). But beware, these methods are NOT virtual methods inherited from MonoBehaviour. In fact, their declaration do not use the override keyword.

In Unity, Start() and Update() are Unity message methods. The term message method is not linked to multiple threads execution, or message queue or asynchronous processing.

Instead:

Update() is always called on the main thread

Update() is executed synchronously

The key point is that the majority of MonoBehaviour instances do not implement Update(). In a typical Unity project:

only about 5% to 20% of MonoBehaviour instances define Update()

the remaining 80% to 95% do not require per-frame execution (trees, buildings, or props)

So, Unity looks for all the MonoBehaviour scripts that implement an Update() function and puts them in a list. This way, when an Update sequence starts, the internal logic looks like this :

foreach script in the Script_with_Update_List:

call script.Update()

Thus using message methods, Unity only performs calls on the objects that require them.

Convenient method

MonoBehaviour inherits from Component and shares the same convenient properties and methods:

Code |

Actual meaning |

|---|---|

gameObject |

reference the gameObject this script belongs |

transform |

reference gameObject.transform |

tag |

reference gameObject.tag |

GetComponent<T>() |

equivalent to gameObject.GetComponent<T>() |

The following statements are strictly equivalent:

Rigidbody rb = GetComponent<Rigidbody>();

<=>

Rigidbody rb = gameObject.GetComponent<Rigidbody>();

Destroy

Inside a Unity script, if you write:

Destroy(this);

the Destroy method is called on the current object, which corresponds to the script component itself. As a result, the script component is removed from the current GameObject. The GameObject and its other components are not destroyed. If you want to destroy the entire GameObject, you must write:

Destroy(gameObject);

Note

The Destroy method does not destroy the object immediately. Instead, Unity marks it for destruction and removes it at the end of the current frame.